Last week there was a bit of a story that went around most media about the head of the Productivity Commission, Danielle Wood, saying that full-time workers would be at least $14,000 better off by 2035 if productivity growth could be boosted from its current low level to its historic average.

What do they mean by this?

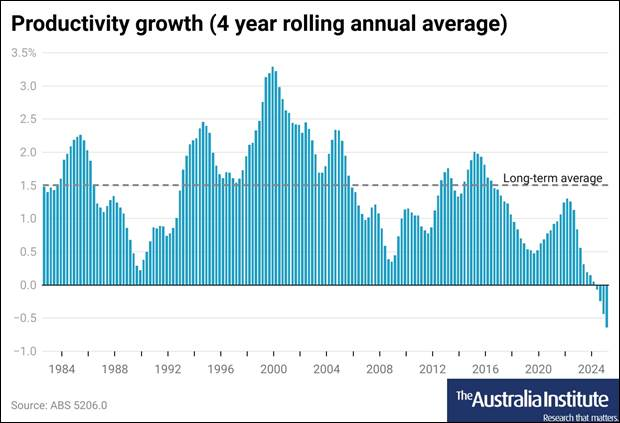

Well, the best way to measure productivity (which is how much output is done in the economy (ie things made, services done) with our time and equipment)) is in a 4 yearly average growth (because the annual figures just around a lot) and as you can see we are currently well down on the historical average.

This is an issue because theoretically when we produce more with our time, that means out living standards should go up – because we should get a pay rise for making/doing more stuff in the same amount of time, and that can happen and not cause inflation because we are (just to say it again) making/doing more stuff with the same amount of time.

Now am as a rule very reticent to call bullshit on anything by the Productivity Commission (that’s a joke for those still yet to have their first coffee), but there are a couple problems with the whole $14,000 better off claim.

The first thing is it is based on wonderful modelling called CGE (Computable General Equilibrium). As Richard Denniss and Matt Saunders wrote in their paper on the topic in January the CGE modelling has more than a few assumptions that that render them pretty limited in their ability to suggest what will happen in the real world. And that is fine, so long as you know that. The problem is CGE modelling in Australia has jumped from universities to the public services (like the RBA and PC and Treasury) and are held up as virtual fact, rather than assumptions.

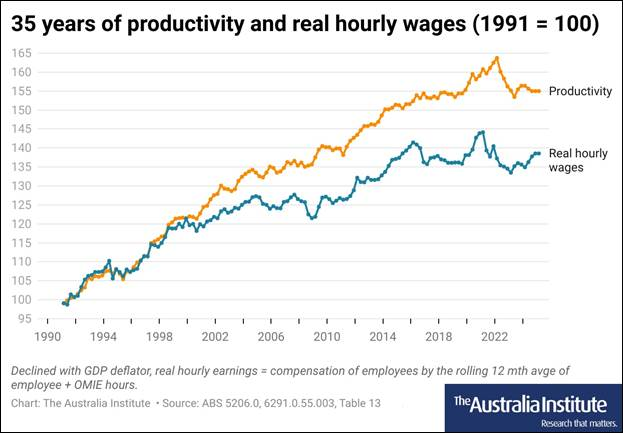

Saying that workers will be $14,000 better off due to better productivity growth assumes that the benefits automatically flow to workers.

The problem is this does not happen. In the real world, the benefits of productivity are fought over in wage negotiations.

As Jim Stanford (former director of the Centre for Future Work) writes in his paper on productivity out today, since 2000 that “productivity grew four times faster since 2000 than average wages adjusted for consumer prices… If workers had received wage increases since 2000 that matched productivity growth, wages would be as much as 18% higher than they are at present – worth $350 per week, or $18,000 per year.”

So sure, productivity should lead to better living standards, but you can’t just assume it will. As Jim writes: “The fruits of productivity growth have been disproportionately captured in the form of business profits, dividend payouts, and executive compensation. It is only through deliberate measures to ensure productivity growth is reflected in improved compensation and conditions for workers that Australian workers can have any confidence their contributions to improved productivity will pay off in better lives.”

No comments yet

Be the first to comment on this post.